I am not into any particular religion but I am open to new things. The other day I stumbled upon a book on Buddhism that I enjoyed. I would like to share what I loved the most.

There is an old Buddhist proverb called “The 84th Problem.” In it, a farmer seeks advice from Buddha on how to solve his problems. After speaking about all of them and being told, one by one, that Buddha can’t offer any help, the farmer grows frustrated and asks why.

“You see, at any point in time, you’ll always have 84 problems in your life,” Buddha replies. “The 84th problem is the key. If you solve the 84th problem, the first 83 will resolve themselves.” Intrigued, the farmer asks what the 84th problem is, and how might he solve it. “Your 84th problem is you want to get rid of the first 83 problems,” Buddha says. “If you understand that life is never without problems, it won’t look so bad.” Kind of cool, no?

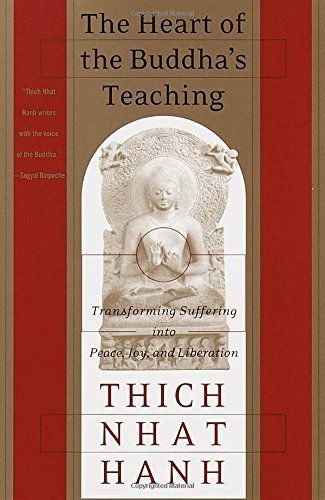

I discovered this proverb five years ago when I was trapped: Is this it? Am I doing enough? Is something wrong with me? This is when I had picked up this book on Buddhism after a friend recommended it.

That so many of us have gone through the same dizzying existential crises doesn’t surprise me. We are living in a crazy time with so many mixed messages: We’re told to strive for more but be content, be content but not complacent, be ambitious but not envious, be grateful but don’t settle, be happy in spite of all of it because life is always hard, every relationship has doubt, every job is difficult, every person has problems. It’s all sound advice but it makes the important task of identifying why you feel uneasy really tricky. And so around we go.

It’s been a couple of years since I played that specific brand of emotional pinball, and I have a theory as to what it was that got me out of it.

Imagine you’re digging a hole in a dirt field. You don’t know what it’s for, you just know you’re supposed to dig it and enjoy it. After a while, your arms grow heavy, your hands begin to blister and every shovelful of dirt feels heavier than the last. You admit to a friend that you’re tired and unhappy. “That’s part of it,” she tells you. “Just trust me!” So you keep going. You try to feel pride for what you’ve accomplished and find solace in the fact that everyone else is digging too, but mostly you’re frustrated and plagued with self-doubt because something just doesn’t feel right.

Now imagine, instead, you were digging that hole to plant a tree, and every time you felt that fatigue, you remembered your efforts were going towards something you recognized, understood and respected.

That metaphor may seem a little weird, but my theory as to how I dismantled the pinball machine is not expressly about finding a purpose. It’s more so about the importance of having something larger to lean on when problems inevitably arise — an answer to the question, “Why am I doing this?” that is not, at its deepest root, “because I’m supposed to.”

That wasn’t an answer I had, nor one I placed much importance in finding. And the result was a life — relationship, job, situation — I liked day-to-day, and which was great on paper, but which I constantly, puzzlingly, struggled to find fulfilling on a broader level. I busied myself trying to snap the hell out of it: Everyone’s arms are heavy, everyone’s hands have blisters, I’m lucky to be digging at all. But those reminders were ultimately Band-Aid solutions. As soon as I heard someone say that her relationship was hard, but she knew it was what she wanted; or heard a writer say that her work was hard, but she knew it was what she wanted to be doing; or heard a person say that Vienna was a hard place to live, but she knew it was where she wanted to be, it would all come crumbling down. Those deeper truths weren’t there for me.

This is hard but, at the end of the day, I’m digging a hole to plant a tree, and that’s important to me. Those six words — “at the end of the day” — eluded me; I could never convincingly apply them to the areas I most wanted to. As in: “At the end of the day, this is the person I want to be with,” or, “At the end of the day, this is what I want to be doing.” It’s a simple phrase that underlines the idea that life’s problems are less daunting when they’re in service of something you believe with gut-certainty. I spent a lot of energy convincing myself that wasn’t true, or that I wasn’t the “type of person” who’d ever be certain of anything, but I was wrong.

So maybe I turned the table over on my life, but I don’t think that’s the only way out of that disquiet. If your answer to why you’re working at your job is: “At the end of the day, it’s paying the bills, and I’m okay with that” — and that feels honest, I say embrace that; let it tether you and accept its associated costs. I’ve seen people do that and they’re much happier for it. But if it doesn’t, and you know it never will?

Find or create a new purpose for what you’re doing that does, and accept the costs that come with that, too. What won’t work are fake reasons that just sound right, because you can’t change your feelings by force. Believe me, I tried.

The why questions aren’t easy to answer, but if I’d placed more value in asking them instead of blaming myself for needing to, I would have identified what was up with me much sooner. My life is different for a while now — a new job, new relationship, new city — and I still have 83 problems, but they no longer make me spiral with self-doubt or question my decisions. As soon as I asked myself what I wanted my problems to be, and began rearranging my life around that answer, the existential hand-wringing of my 84th fell away.